As Jonathan is fond of saying: Drugs are poisons. It is only through an arduous process of testing and refinement that a drug is eventually transformed into a therapy. Much of this transformative work falls to the early phases of clinical testing. In early phase studies, researchers are looking to identify the optimal values for the various parameters that make up a medical intervention. These parameters are things like dose, schedule, mode of administration, co-interventions, and so on. Once these have been locked down, the “intervention ensemble” (as we call it) is ready for the second phase of testing, where its clinical utility is either confirmed or disconfirmed in randomized controlled trials.

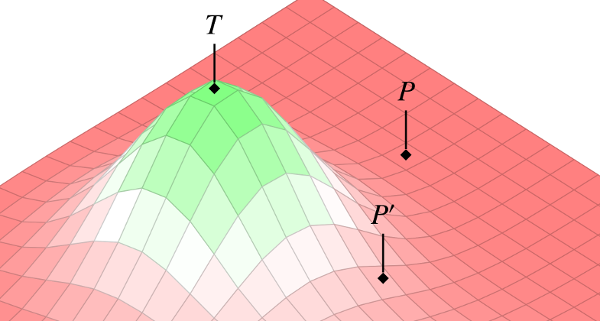

In our piece from this latest issue of the Kennedy Institute of Ethics Journal, Jonathan and I present a novel conceptual tool for thinking about the early phases of drug testing. As suggested in the image above, we represent this process as an exploration of a 3-dimensional “ensemble space.” Each x-y point on the landscape corresponds to some combination of parameters–a particular dose and delivery site, say. The z-axis is then the risk/benefit profile of that combination. This model allows us to re-frame the goal of early phase testing as an exploration of the intervention landscape–a systematic search through the space of possible parameters, looking for peaks that have promise of clinical utility.

We then go on to show how the concept of ensemble space can also be used to analyze the comparative advantages of alternative research strategies. For example, given that the landscape is initially unknown, where should researchers begin their search? Should they jump out into the deep end, to so speak, in the hopes of hitting the peak on the first try? Or should they proceed more cautiously–methodologically working their way out from the least-risky regions, mapping the overall landscape as they go?

I won’t give away the ending here, because you should go read the article! Although readers familiar with Jonathan’s and my work can probably infer which of those options we would support. (Hint: Early phase research must be justified on the basis of knowledge-value, not direct patient-subject benefit.)

UPDATE: I’m very happy to report that this paper has been selected as the editor’s pick for the KIEJ this quarter!

BibTeX

@Manual{stream2014-567,

title = {The Landscape of Early Phase Research},

journal = {STREAM research},

author = {Spencer Phillips Hey},

address = {Montreal, Canada},

date = 2014,

month = jul,

day = 4,

url = {https://www.translationalethics.com/2014/07/04/the-landscape-of-early-phase-research/}

}

MLA

Spencer Phillips Hey. "The Landscape of Early Phase Research" Web blog post. STREAM research. 04 Jul 2014. Web. 06 May 2024. <https://www.translationalethics.com/2014/07/04/the-landscape-of-early-phase-research/>

APA

Spencer Phillips Hey. (2014, Jul 04). The Landscape of Early Phase Research [Web log post]. Retrieved from https://www.translationalethics.com/2014/07/04/the-landscape-of-early-phase-research/